New York City Financial Institution Data Center Heat Rejection on Rooftop

Heat Exchanger Pre-Cooling

To keep the data center operating, since there was no room for additional rooftop condensers, the financial institution needed to find a way to get more cooling out of the condensers it did have by bringing down the inlet air temperature.

Challenge:

To boost the capacity of the existing rooftop condenser units for an 80,000 square foot urban data center so the company could add more computing equipment without having to shut down the data center during summer heatwaves.

Solution:

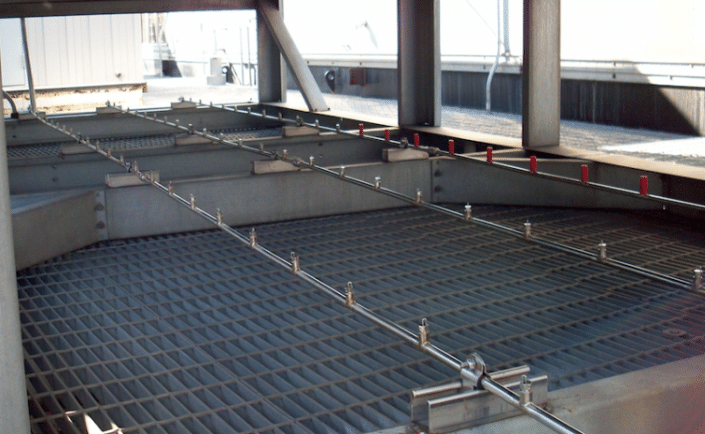

Install MeeFog fogging units on the eight existing rooftop dry cooler condenser units. Operate the MeeFog units when glycol temperatures exceed 100°F.

The Installation:

Rural data centers can pull in enough outside air to keep the data center cool. In this case, the data center is in the middle of a dense urban area where the streets and brick buildings absorb the heat day after day and don’t fully cool down at night, gradually raising the temperature inside the building. To make things worse, while the urban ambient temperatures themselves are higher than the surrounding countryside, the rooftop temperatures can exceed the ambient temperatures by another ten degrees.

The data center uses an indirect cooling system with CRAC units in the white space. Glycol runs through heat exchangers in the CRAC units and is then pumped to rooftop units where the glycol is recondensed and the heat dissipated into the outside air. When the data center went through a major upgrade which added to the heat load, there was enough room on the roof to install five additional condensers to supplement the eight already in use. This arrangement works for most of the year, but for a week or two each summer it does not. The cooling system operates properly as long as the glycol temperature can stay below 100°F. When it exceeds that temperature, the cooling system can trip off line.

“We have dry coolers on the roof, so we don’t have the benefits of evaporation,” says the data center’s assistant chief engineer. “If we have 1000 tons of refrigeration at 100°F, when it goes to 110°F capacity drops and we are just shy of what we need. On very hot days when it gets above 110°F on the roof, which we reached about ten days last year, the units would have tripped offline on high head pressure.”